|

|

|

Cultural Lanscapes

Walking the Cultural Landscapes of the Northern Kinneret

Yael Alef [1]

|

“Five gospels record the life of Jesus. Four you will find in books and one you will find in the land they call holy. Read the fifth gospel and the world of the four will open to you”.

Bargil Pixner [2]

|

|

|

The landscapes of the Kinneret are spread out in a panorama toward the east, from the Mount of the Beatitudes.Photograph: Yael Alef 2007

|

The landscapes of the Sea of Galilee, which are surrounded by the steep arid slopes of the Golan mountains to the east and the cliffs of the Arbel to the west, unfold before the visitor to the Mount of Beatitudes. The Korazim Plateau slopes down, below his feet, leaving a narrow green strip of beach where there are the remains of fishing villages from the Roman period, Byzantine churches and anchorages. These landscapes reflect one of the most fascinating dramas in the history of western civilization. Jesus and his disciples walked the regions of the Galilee and the shores of the Kinneret, and it was there that the ideas that constitute the doctrine of Christian benevolence first took shape. It seems that these landscapes have changed only slightly since the time when Jesus was active in them, healing the sick and resurrecting the dead, working miracles and preaching sermons and parables to his followers. The stories of the place echo for us the events that have fascinated pilgrims and tourists the world over for hundreds and thousands of years.

The submission of the nomination of the Christian sites in the Galilee to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Heritage list calls for another reading and interpretation of the gospel landscapes, which play a role in preserving a long tradition of pilgrims and visitors who wish to walk in the footsteps of Jesus and personally experience the stories of the gospel in the places where these events transpired.

What is the universal value of the cultural landscapes in the northern Kinneret that stands as the basis for submitting its nomination to the exclusive list of UNESCO’s world heritage sites?

|

The Cultural Landscapes of the Northern Kinneret are Nominated for Inscription in the World Heritage List

|

|

UNESCO encourages identifying, protecting and preserving cultural and natural heritage throughout the world. This policy is enshrined in the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage of 1972. Israel became a signatory of this convention in 2000 thus joining 159 other nations that are committed to ensuring the safeguarding of their natural and cultural heritage. The Israeli committee to UNESCO decided to promote the submission of the Christian sites in the Galilee for nomination to the list. The Conservation Department of the Israel Antiquities Authority took it upon itself to coordinate and prepare the nomination file. The file was compiled with the help of a team of experts in the fields of history, archaeology, and geography, and in cooperation with the churches, the National Parks Authority and the local councils.

The proposed declaration includes churches in Nazareth, Kafr Kanna and Nein and the cultural landscapes of the northern Kinneret, among them Capernaum, the Korazim National Park, Tabgha, Mount of the Beatitudes and Magdala.

|

The Landscape in the Story and the Narrative of the Landscape – The Relation between Reading the Landscape and Reading the Story

|

|

|

The shore of the Kinneret in the vicinity of Capernaum preserves the landscapes where pilgrims walked for hundreds of years in their spiritual journey to discover the gospel.Photograph: Yael Alef 2007

|

For many people the Holy Land is the land of the Holy Scriptures. The landscape takes on a profound and unique meaning from the way it is defined and read in the New Testament.

“And he went about all Galilee teaching in their synagogues and preaching the gospel of the kingdom and healing every disease and every infirmity among the people.” (Matthew 4:23)

For most of his life Jesus worked in the Galilee. These landscapes, especially in the northern Kinneret, are entwined in the four stories of the gospel which open the New Testament: Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Despite the fact that the gospels were not written as historical texts, they reflect the reality of a place. In its descriptions of Jesus, who wandered between Nazareth and Capernaum, Korazim and Bethsaida, in the mountains and along the shore of the Kinneret, the nature of the geography of the Galilee in the first century CE is revealed.

In his writings about the fifth gospel, the priest and scholar Bargil Pixner contends that by reading the physical landscape of the country one can better understand the stories of the gospel. This approach was already accepted in the fourth century. For example, in the Onomastikon, Eusebius of Caesarea identifies sites that are mentioned in the Bible and the New Testament with existing settlements and places. This is based both on historic sources and on the sites themselves. A similar point of view encouraged many scholars in the nineteenth century to travel the land using the Bible and the New Testament as tour guides such as the father of biblical geography, Edward Robinson, did.

Who of us has not heard of Jesus walking on water and feeding 5,000 people with five loaves of bread and two fish some two thousand years ago? One can also assume that today most visitors to the northern Kinneret, whether they are faithful Christians or the occasional tourist, will identify the places with the miraculous deeds that are known from the New Testament.

The landscapes that are mentioned in the stories of the gospel define the geographic region where Jesus worked. Thus abstract ideas are anchored in concrete events and tangible locations, which contribute to preserving the messages of the story. The landscapes of the Kinneret are a clear example of the way in which a connection of ideas to a time and a place become a myth. Nonetheless, the valleys, the mountains and the shores of the Kinneret along which Jesus and his disciples walked are not just a backdrop for the events. For the Christian believer these are holy places where the Lord was revealed. Therefore these landscapes have become an integral part of the spiritual traditions and a focal point for the pilgrimage movement.

|

The Landscape in the Story – The Kingdom of the Lord is Like a Grain of a Mustard Seed

|

|

|

The Korazim Plateau with its rocky landscapes reflects the desolate places that lie outside the precincts of the settlement, where Jesus would usually walk. Photograph: Yael Alef 2007

|

The Galilee landscapes are manifested in the stories of the gospel in two ways: one, in the locations where the events of Jesus’ life occurred and two, in the parables and metaphors. Both of them illustrate the way of life of the local farmers and fishermen and the characteristics of the region. The use of the local animal and floral imagery that are known to his listeners, with the exposed rocky soil and the annual plants, accentuate the social and religious messages. For example, with the coming of spring, when the slopes of the Korazim Plateau are flowering with carpets of yellow mustard, the parable of the mustard seed appears in front of us:

And he said, "With what can we compare the kingdom of God, or what parable shall we use for it? It is like a grain of mustard seed, which, when sown upon the ground, is the smallest of all the seeds on earth; yet when it is sown it grows up and becomes the greatest of all shrubs, and puts forth large branches, so that the birds of the air can make nests in its shade." (Mark 4:30-32)

It seems that Jesus preferred to go to the wild fields outside the settlements in order to deliver his sermons. A short walk from Capernaum brought him and the crowds of people to the top of the hill where he sat and delivered the “Sermon on the Mount”. The sermon is known as one of the high points in the gospel summarizing the central tenets of the Christian belief of charity, compassion and benevolence. In this case Jesus chose the birds in the sky and the lilies of the field in order to illustrate the importance of having faith in the Lord:

“Look at the birds of the air: for they neither sow nor reap nor gather into barns and yet your heavenly father feeds them… and why are you anxious about clothing? Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow; they neither toil nor spin.” (Matthew 6:26-28)

In the “Parable of the Sower” the special characteristics of the Galilean landscape are described – the meeting between the cultivated plots and the rocky fallow ground. The scene portrays Jesus sitting on the edge of the water and when the masses crowd around him he goes down to a boat and preaches to the people who are standing along the shore:

“A sower went out to sow. And as he sowed, some seeds fell along the path, and the birds came and devoured them. Other seats fell on rocky ground, where they had not much soil, and immediately they sprang up, since they had no depth of soil, but when the sun rose they were scorched; and since they had no root they withered away. Other seats fell upon the thorns, and the thorns grew up and choked them. Other seats fell on good soil and brought forth grain, some hundred fold, some sixty, some thirty. He has ears, let him hear.” (Matthew 13:3-9

|

|

|

Jujube trees at Korazim. The Latin name of the jujube tree is Zizyphus Spina-christi (the messiah’s thorns) and refers to the crown of thorns in the story of Jesus’ crucifixion. Photograph: Yael Alef

|

The books of the gospel reveal an understanding of the local wind regime and illustrate the same connection that resembles reality, this time of the climatic conditions that are characteristic of the lake. In the story of the miracle of Jesus calming the squall, it is described that toward evening, when they are sailing to the other side of the lake:

“And a great storm of wind arose, and the waves beat into the boat, so that the boat was already filling.” (Mark 4:37)

Storms such as these are known to occur in the Kinneret during the afternoon hours, when the west wind blows, striking the small body of water and creating storms of surprising intensity. The strong winds prevent Jesus’ disciples from sailing back to Bethsaida, as described in the miracle of walking on water:

“And when evening came, the boat was out on the sea, and he was alone on the land. And he saw that they were distressed in rowing, for the wind was against them. And about the fourth watch of the night he came to them, walking on the sea.” (Mark 6:47-48)

These are just a few of the examples of how the landscape is expressed in the stories of the gospel. But where can we read the Christian narrative in the landscape itself?

|

The Story in the Landscape – Christian Traditions in the Landscapes of the Northern Kinneret

|

|

|

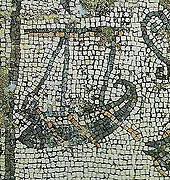

A mosaic depiction of a boat, Magdala, first century CE. In the vicinity of Magdala, also known as Migdal Nunia, an ancient anchorage and fishing boat were uncovered. Photograph: Yossi Stepansky 2007

|

One hundred years of research and archaeological excavations in the region have not uncovered artifacts that are directly connected to Jesus and the apostles or of Christian activity in the region from the first century CE (the time of Jesus’ ministry according the gospel). Nonetheless, we can learn about the reality that is described in the gospel from the finds that were exposed at Capernaum, and especially in the center of the city of Magdala, as well as in the many anchorages that are scattered along the shores of the lake. That being the case, we need to draw a distinction between the finds of the first century CE, in which there is no direct evidence of Jesus’ activity, and the unequivocal evidence of the Christian traditions that developed from the fourth century onward.

The ‘holy geography’ developed during the Byzantine period when Christianity became the official religion of the empire, at which time the places that marked the events of Jesus’ life and his disciples were first identified and sanctified. These became pilgrimage sites for those who wished to sense the atmosphere that prevailed among the public that stood on the shore and heard the homilies and for those who searched for the house of Simon (Peter) in Capernaum. The remains of churches from this period, which commemorate the events of the gospel stories, have been exposed in the Church of the Multiplication of the Loaves and the Fishes, the Church of Peter’s Primacy (Mensa Christi), the chapel on the slopes of Mount Beatitude, the church above Simon’s (Peter) house in Capernaum, and Kursi. Another source of knowledge about the development of holy places is the travel descriptions of the pilgrims who visited the land beginning in the fourth century CE.

|

|

|

The Church of the Peter’s Primacy at the shore of the Kinneret in Tabgha, was built on top of the remains of the Byzantine church and ancient stone quarries.Photograph: Itamar Greenberg 2008

|

The intensive Christian activity in the northern Kinneret was renewed in the nineteenth century and today there are a number of churches and religious orders that are active in the region: the Benedictines at Tabgha; the Franciscans at Magdala, the Church of Peter’s Primacy and in Capernaum; the Greek Orthodox at Capernaum; and the Franciscan Sisters on the Mount of Beatitudes. The holy sites answer the human need of the pilgrims for a palpable experience and through it connect to the symbolic significance of the place.

The landscapes of the Tabgha Valley demonstrate the interpretation of the landscape in light of the Christian narrative. Tradition associates Tabgha with a number of the important events in the books of the gospel such as: the call for apostles, the miracle of the multiplication of the loaves and the fishes, the Sermon on the Mount, and Jesus’ appearance before his disciples after his death and the transfer of the primacy to his disciple Simon (Peter).

Tabgha is a corruption of the Greek name Heptapegon, which means “seven springs”. To this day this part of the Kinneret is still known as one of the most abundant fishing regions, thanks to the hot springs that attract fish there. Here the tradition about Jesus took hold, when he was:

“…passing along by the Sea of Galilee, he saw Simon and Andrew the brother of Simon casting a net in the sea; for they were fishermen. And Jesus said to them, ‘Follow me and I will make you become fishers of men.’” (Mark 1:16-17)

|

|

|

A mass being celebrated by Christian pilgrims along the water’s edge at Tagbha, in their spiritual journey to discover the gospel in the landscapes of the Holy Land.Photograph: Itamar Greenberg 2008

|

A small anchorage that was used by fishermen in antiquity was discovered in this spot. In the stories of the gospel there are many other references made to the fisherman’s way of life such as Bethsaida, whose name alludes to the hunting of fish and Magdala, also called Midgal Nun, that is the “Fish Tower”, and what can be more symbolic than the common English name (St. Peter’s fish) that has been given to the tilapia fish.

The fertile valley, with its abundant springs, was an important part of the agricultural hinterland of the Capernaum. The picture that is painted of an uninhabited agricultural region matches the descriptions of the region in the books of the gospel. The natural area was suitable for the gatherings of the multitude of believers who thronged after Jesus:

“When it was evening, the disciples came to him and said, ‘This is a lonely place, and the day is now over; send the crowds away to go into the villages and buy food for themselves.’ Jesus said, ‘They need not go away; you'll give them something to eat.’ They said to him, ‘we have only five loaves here and two fish.’ And he said, ‘Bring them here to me.’ then he ordered the crowds to sit down on the grass; and taking the five loaves and two fish he looked up to heaven, and blessed, and broke and gave the loaves to the disciples, and the disciples gave them to the crowds. And they all ate and were satisfied. And they took up twelve baskets full of the broken pieces left over. And those who ate were about 5,000 men, besides women and children.” (Matthew 14:15-21)

|

|

|

Duccio, tempera on wood 1308-1311, Jesus beckoning to Simon and AndrewSource: (Wikimedia Commons)

|

On a journey in the footsteps of Jesus, the traveler Egeria describes Tabgha at the end of the fourth century:

“And in the same place by the sea is a grassy field with plenty of hay and many palm trees. By them, are seven springs each flowing strongly. And this is the field where the Lord fed the people with the five loaves and two fishes. In fact the stone on which the Lord placed the bread has now been made into an altar. People who go there are take away small pieces of the stone to bring them prosperity and they are very effective. Past the walls of this church goes the public highway on which the Apostle Matthew had his place of custom.”

The altar and the Roman road that are mentioned in Egeria’s diary were discovered in the archaeological excavations that were first conducted at the site in 1898. During the course of the excavations the remains of a small church from the fourth century were exposed that commemorated the miracle of the multiplication of the loaves and fishes and above it were the remains of a magnificent basilica from the fifth and sixth centuries, which is decorated with the famous mosaic depicting the basket with the loaves of bread and the fish. Since its exposure this mosaic has become one of the most well-known symbols of the Holy Land in Christendom. In 1980 a modern church building was erected along the lines of the ancient basilica and the altar stone and the ancient mosaic pavements are incorporated within it.

|

|

|

The Tabgha Valley, then as now, the cultivation plots in the valley stand out against the background of yellow rocky hills Photograph: Itamar Greenberg 2008

|

The ancient Christian traditions identify the Mount of the Beatitudes, which is north of the valley, as the place where the Sermon of the Mount was delivered. The name Beatitudes is taken from the word beatus (meaning “blessed” in Latin) with which the first eight verses of the sermon begin. At the foot of the mountain are the remains of a Byzantine church that commemorates the sermon. A little further on from there, above the bathhouse of Job, is a cave about which the traveler Egeria says “the messiah went up a mountain next to the cave and delivered the Sermon of the Mount.” Between the years 1936 and 1938, the octagonal chapel was constructed at the top of the hill looking out over the landscapes of the Kinneret and the places where Jesus and the Apostles were active. In ancient traditions “the mountain” is an isolated place where would one go for inner contemplation. It seems that today also, the quiet there preserves something of the echoes of that same, famous sermon.

|

The Cultural Significance of the Landscapes of the Northern Kinneret in the Present

|

|

|

The stone altar and the mosaic of the fish and loaves of bread in the Church of the Miracle of the Multiplication of the Loaves and the Fishes at Tabgha.Photograph: Yael Alef 2007

|

Different narratives that are connected to the Kinneret’s landscape create different layers of meaning for a variety of communities. For most of the Israelis, for example, these landscapes are associated with ancient Jewish heritage and the new settlement there, and with memories of trips and holidays on the shores of the lake. The Christian cultural significance of the landscapes of the northern Kinneret reveals another layer which facilitates their understanding in the context of universal heritage.

The Kinneret’s landscapes constituted a source of inspiration that has enriched western civilization with countless literary and artistic creations; hence their importance also for those who are not believers of Christianity.

A panorama of the gospel landscapes lies in front of the visitor to the Mount of the Beatitudes and evidence of the Christian traditions are spread out before him. The landscapes are integrated in the story just as the Christian narrative is engraved in the landscape, in the feet of the tens of thousands of pilgrims for more than 1,600 years. The remains of the “holy history” are hidden in the “holy geography” in the Galilee. Here very powerful connections are created: of the tangible local landscape, with the intangible spiritual aspect; of the worldly with the sacred, of the past with the future. The ongoing dialogue that exists simultaneously between the landscapes in the stories of the gospel and the narrative of the landscape, which is rewritten generation after generation, is of universal value and it is the basis for submitting the nomination of the Christian sites in the Galilee for inscription in the World Heritage List.

|

|

The landscapes of the northern Kinneret still maintain their historic fabric and authentic character but they are frequently threatened by development initiatives that are likely to damage the delicate and sensitive fabric of the landscape. Recognizing the value of the sites is a condition to preserving them. Submitting the nomination is a stage in creating a basis for the safeguarding and preservation of the sites and the cultural landscapes of the northern Kinneret.

-------------------------------------------------------

[1] The author of this article, together with Michael Cohen, coordinated the compilation of the nomination file of the Christian sites in the Galilee for inscription in the UNESCO list of World Heritage.

[2] A Benedictine priest who lived in the Tagbha monastery and dedicated his life to locating the places where the events that are described in the books of the gospel occurred.

Pixner, B. (1992). With Jesus Through Galilee According to the Fifth Gospel. Rosh Pina.

|

|

Sources for Review

This article is based on material from the nomination file of the Christian sites in the Galilee for the World Heritage List of UNESCO (2008), and particularly on the chapters which deal with the cultural landscapes of the northern Kinneret that were written with the help of Dr. Irit Amit, Aviad Sar Shalom, Yossi Stepansky and Dr. Yaki Ashkenazi.

-----------------------

November 2008

|

|

|

|

|